A Proto-Type Mac OS

- A Proto-type Mac Os 7

- A Proto-type Mac Os Operating System

- A Proto-type Mac Os Model

- A Proto-type Mac Os X

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple in January 1997, he was ready to clean house in the design department. The computers Apple released were ugly pizza boxes like the LC series. Jony Ive, who had arrived at Apple five years before Jobs’ return, walked down the hall with a resignation letter in his pocket to his first meeting with Jobs. The letter was never accepted because the Industrial Design Group was producing some amazing work that was locked away in the back room. What was the work that saved Jony’s job? What were the designs sitting on the workbench that so impressed Steve Jobs?

“What were the designs that saved Ive’s job?”

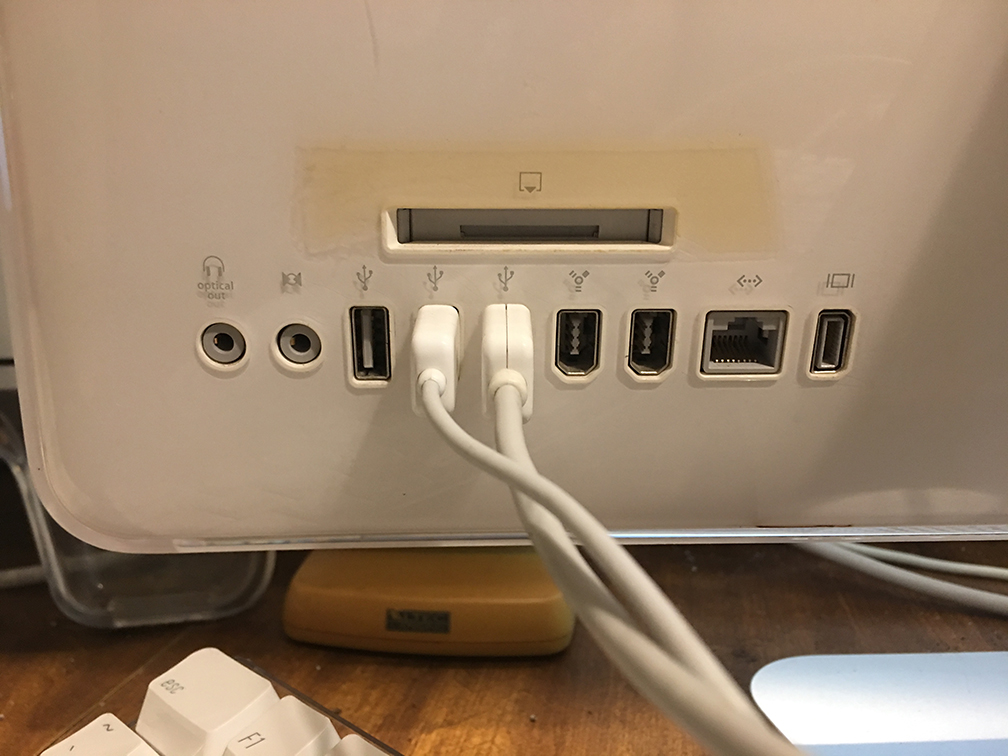

No doubt that this is a testing unit for before the MacBook Pros were released. In June 2005 Apple gave out Intel Developer machines to developers. So of course they could have had Intel machines produced, in fact Jobs stated that they did have OS X running on Intel machines as far back as Mac OS X 10.0!

Release notes Twiggy Mac OS is a development pre-release used with the 5.25' Twiggy prototype Macintosh. This version will not run on a normal Macintosh or emulator, and used Apple's 5.25' Twiggy floppy disk. A special Twiggy Macintosh emulator is included so you may try it for yourself. Liked this video? Subscribe for more: Today, we'll be diving into a prototype version of Macintosh System Software 1.

A rare look into early Apple prototypes is provided by the book, “Apple Design: The Work of the Apple Industrial Design Group” by Paul Kunkel from January 1997. It gives unprecedented access to prototypes and lost designs from this era. Just before Jobs return there were two major design studies, Pomona and Spartacus, that resulted in physical prototypes. This was the work that so impressed Jobs that he kept Ive and the rest of the team.

I’ve always had a bit of an obsession with one of the computers from the Pomona design series. It's the “Curved Wood and Black Metal concept with detachable speakers”. Its curving lines and use of wood were so radically different from anything on the market in 2001, when I got the book.

I love turning ideas into physical objects, and for years I played around with ideas for reproducing the iconic curves of this design. Steam bending wood exceeded the limits of my small basement shop. It wasn’t until a Maker Space moved in near me that I had the tools recreate this iconic prototype. The laser cutter was the tool that finally gave me the skills to recreate this prototype and explore a path-not-taken in personal computing.

Robert Brunner was the design chief at Apple from 1989 to 1996. His leadership was visionary and established the Apple Industrial Design Group that has created all of the recent iconic product lines. He created a design brief, Pomona, calling for a rethinking of the personal computer. The brief called for designs that redefined home computing, employing new materials (leather, wood) and new shapes that would blend into the home environment. It was to be a desktop Mac with a minimum footprint that did not conform to Apple’s existing design language. It would also, for the first time, combine the thin LCD screens with the power of a desktop CPU. The design was to explore “minimum footprint opportunities. As remembered by Brunner...

“Pomona concepts should not necessarily follow Apple’s existing product language. Instead they should project high-performance values with compelling vision, provocative forms, rich materials unique configurations, and added functionality using miniature components.”(1)

There are only two images of this prototype (see above). One from the Apple Design book and another that I had to dig up at the Library of Congress from a very old copy of MacUser magazine from January 1994 in the article “Why 2004 won’t be like 1994” by Jon Zilber.

From these two images I was able to design to create the design in Illustrator and export to the laser cutter. Images and details of the build are here.

In recreating this machine, I didn’t want to create just a shell, I wanted to produce a working late 1990’s era Mac. That meant a computer running Mac OS 7.5.5 or OS 8. The heart of the machine is an Intel NUC running Ubuntu with the MacBuntu skin to make it look like OSX. It's also running two emulators. SheepShaver which emulates a PowerPC setup with OS9 and Basilisk II which emulates 68040 with Quadra 630 ROM that runs both System 7.5.5 and OS8. I really wanted to get a working copy of Apple’s lost OS, Copland, but couldn’t find a working install. The screen is an iPad 2 screen with 1024x768 with an HDMI adapter that picked up on Alibaba.

Here are some images (more here) of the finished prototype running OS 7.5.5.

The work on the Pomona design series lead to the prototypes for the Twentieth Anniversary Mac. Jony Ive led this work and the 20th Anniversary Mac was his first released design. It was released on in January 1997, the same month Jobs returned to Apple with the Next acquisition.

This was an incredibly rewarding build that drove me to pick up an entirely new set of skills that I’ve applied to many other projects. My thanks to the Apple Industrial Design team, even your discarded projects are inspiring.

- Quote from “Apple Design: The Work of the Apple Industrial Design Group” by Paul Kunkel

With the Motorola 680×0 architecture running out of steam and Motorola’s 88000 making haste slowly, Apple had to look a bit further afield for its next processor architecture. Here’s how IBM’s RISC project became the heart of the Mac.

Early RISC Work at IBM

The story of the PowerPC began in the early seventies when John Cocke and his team at IBM began designing one of the earliest RISC processors, the 801. By the mid-1970s it was believed that microprocessors had become as complex and feature rich as they ever would, so further advances would have to come in the form of miniaturization or fundamental shifts in thinking about processor design.

John Cocke studied several processor designs of the day and realized that the more complex commands in ordinary processors were rarely used and only added complexity to the chip, which served to slow it down. As a result of eliminating seldom used instructions, the IBM 801 had slightly less than a hundred commands, while Intel’s 8086 had over 400.

The 801 was ready for release in 1977 and performed at 15 MIPS, about as fast as the Quadra 605 that Apple had introduced more than a decade later.

The first product that used the 801 was the IBM RT PC, which used the chip with a standard PC AT bus. Few companies adopted the RT PC or 801 until 1990, when IBM released PowerPC.

Apple Looks at RISC

Apple reached the same conclusions about RISC design that IBM had in the mid-seventies. The Motorola 680×0 processor Apple used in its Macintosh computers was beginning to show its age. The promised revision to the line, the 68040, was pushed back further and further, and Apple had little confidence that Motorola would be able to consistently produce processors competitive with the next generation x86 processors.

In 1986, Apple planned a response to the stagnating 68000 line and started a project to replace the processor. Incredibly ambitious, the project, code named Aquarius, would create a four core RISC processor. A team of fifty engineers was assembled, and John Sculley even authorized the acquisition of a Cray supercomputer to aid in designing the processor, yet little progress was made.

Hugh Martin, a microprocessor expert personally recruited by John Sculley, was tapped to lead the successor to Aquarius, Jaguar (right). Jaguar would use a preexisting RISC design to create a multiprocessor workstation. The machine was to be a showcase of top of the line technology. Martin selected the Motorola 88100 processor and planned to use four in the new machine.

Even before NeXT started creating NeXTstep, Apple was creating an operating system based on the microkernel Mach, named Pink. The microkernel design meant that the kernel handled only very basic exchanges between the hardware and other pieces of software. All the other services and software were divied up into servers, which were all capable of communicating with each other. The chief advantage of the microkernel design was stability. If a server crashed, it could be restarted without restarting the entire system. (See Full Circle: A Brief History of NeXT for more information on NeXT, NeXTstep, and servers.)

A Proto-type Mac Os 7

The chief weakness of the powerful Jaguar workstation was that it was totally incompatible with older Mac OS software – and the Mac OS itself. The engineers decided not to emulate the Mac OS because it would discourage developers from adopting the new operating system.

Emulation

During a ski trip in Reno, Nevada, a group of Apple engineers led by Jack McHenry decided to start a project that would make the Jaguar machine compatible with older software. Work began almost immediately when the engineers returned to Apple, and the project was named Cognac. It was stopped when the company moved away from the 88k processor.

A Proto-type Mac Os Operating System

Jaguar would have to find a new processor. Several prototype boards were created around ARM (which Apple owned in part) and MIPS processors, but they were not adopted.

Gary Davidson, an expert in emulation, wrote an emulator for every new processor that was adopted. His software was based on the 90/10 theory of emulation. The theory centered around the observation that 10% of the software was being used 90% of the time, which meant that only a small portion of a program had to be run at a time. As a result, the emulators he created were very fast, typically as fast as a Mac IIci running 68k software.

PowerPC and the Mac

The 88100’s only major customers were Apple Computer and Ford. Once Apple dropped the chip, so did Ford, and Motorola was unable to afford continuing development. IBM, after being shown the Mac OS running on Intel hardware (part of the Star Trek project), approached Apple about porting the Mac OS to run on the PowerPC 601 CPU, the processor was used in the RS/6000 workstation.

On July 3, 1991, IBM offered to help Apple finish Pink, its object oriented operating system for Jaguar, if Apple would adopt the PowerPC processor. Motorola was brought in to help manufacture the new processors, and the deal was sealed, creating the Apple-IBM-Motorola (AIM) alliance.

IBM began refining the PowerPC design and split it into two different classes. The PowerPC processor used in the RS/6000 series (actually a collection of processors on one die) was renamed POWER1, and the processors destined for consumer class workstations and embedded apps were named PowerPC.

The first commercially available PowerPC processor was the 601, and it was the one adopted by Apple for its earliest PowerPC computers. The chief difference between the new PowerPC and POWER1 was the size of the processor – the PowerPC was dramatically smaller and ran cooler.

A Proto-type Mac Os Model

In order to simplify the process of bringing the partially completed Pink operating system to the PowerPC processor, IBM made the PowerPC’s bus compatible with the Motorola 88100 processor, allowing Apple to get by with only a partial rewrite of the lowest levels of the operating system.

Cognac and Jaguar, renamed Tesseracht, raced to produce a finished product. The hardware designs for both machines were slightly modified Jaguar designs, and the biggest hurdle was software.

Breakthrough

Cognac had its breakthrough during the Christmas holiday (while the Tesseracht team was on vacation) when Gary Davidson completed the 68k emulator for the PowerPC (PPC) and ran the Mac OS in emulation on the prototype (housed in an LC case, it was named the RISC LC or RLC).

A Proto-type Mac Os X

RLC performed better than the recently released Quadras and would perform even better with native PPC software. The scope of the team changed from hardware and emulation design to basic software development, as portions of System 7 were rewritten for the PowerPC processor.

As the Mac OS was prepared for PowerPC, a new kind of app was created so software developers could release one file for both PowerPC and 68k users. Cognac created “fat” binaries, program files that contained both PowerPC and 68k code, allowing the same program to run natively on new Macs and old.

By March of 1992, Pink was stagnant, Tesseracht was canceled, and some of the engineers moved over to Cognac to complete the project in time for the new deadline of January 24, 1994 – the tenth anniversary of the release of the original Macintosh.

Power Macintosh

In 1993, three models were readied for release. The least expensive was code named Piltdown Man for the hoax of a half-man/half-ape found in Britain at the turn of the century. Piltdown Man would be housed in a Quadra 610 case. The midrange PowerPC-based computer was code named Carl Sagan, and it was in a Centris 650 case, and the top of the line machine was code named Cold Fusion.

Sagan took issue over the use of his name and sued Apple to prevent the company from using it. Apple complied and renamed the machine BHA, for Bone Headed Astronomer or Butt-Head Astronomer. Sagan threatened to sue again, so Apple renamed the prototype LAW (for Lawyers Are Wimps).

The new product line was named Power Macintosh. It was announced on time, and the machines (the 6100, 7100, and 8100) that shipped in March 1994 outperformed comparable Pentium-based computers.

Further Reading

- The PowerPC Triumph, Dr Bott

- PowerPC, Wikipedia

- IBM Fellow John Cocke passed away on July 16th, IBM

- John Cocke, Wikipedia

- RISC, Wikipedia

- IBM RT, Wikipedia

- Motorola 8800, Wikipedia

- IBM RS/6000, Wikipedia

Bibliography

Some of the sources used in writing this article:

- Apple: The Inside Story of Intrigue, Egomania, and Business Blunders, Jim Carlton

- Infinite Loop, Michael Malone

- The Second Coming of Steve Jobs, Alan Deutschman

- Apple Confidential 2.0, Owen Linzmayer

- Odyssey: Pepsi to Apple . . . a Journey of Adventure, Ideas & the Future, John Sculley

Keywords: #powerpc #powermacintosh #aimalliance

Short link: http://goo.gl/06zizn

searchword: ibmapplerisc